Mask it or casket

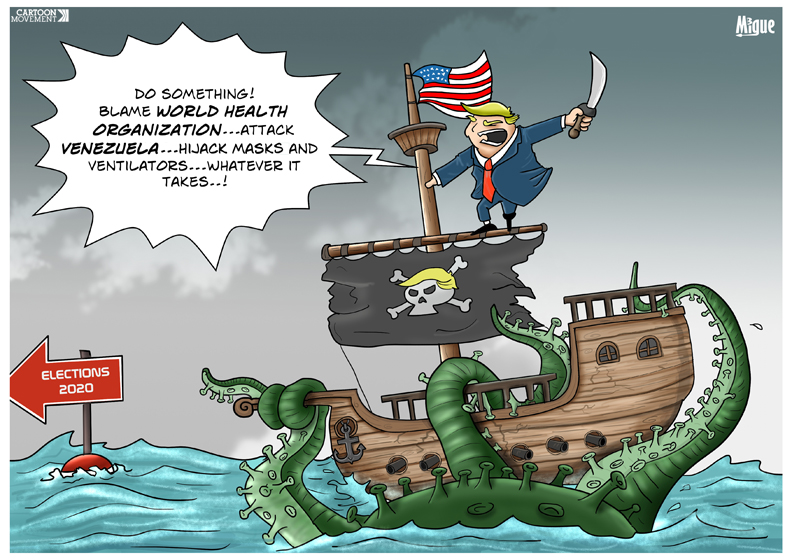

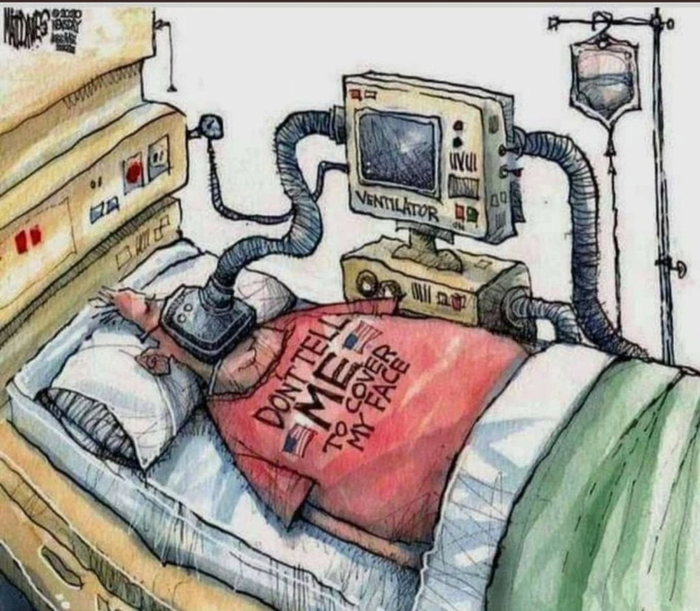

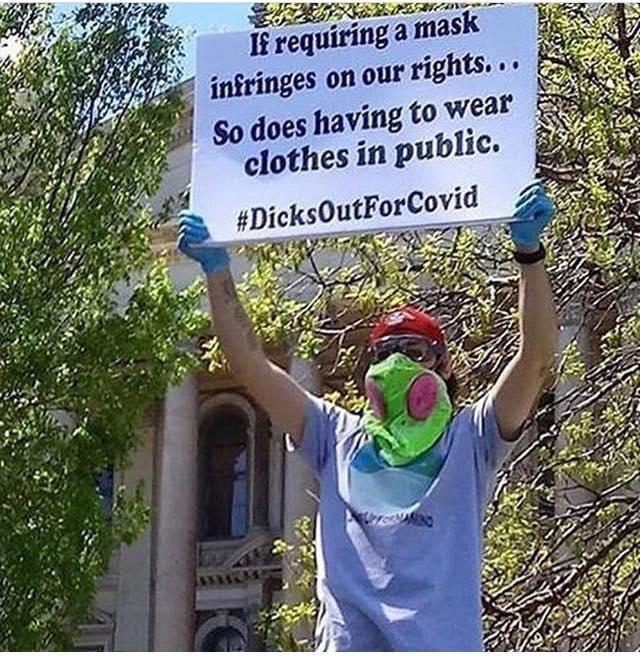

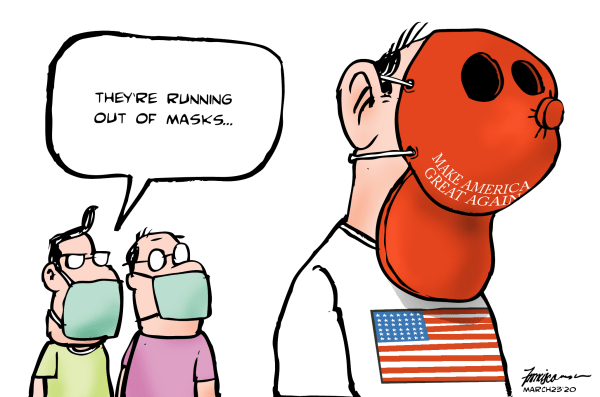

Wearing a mask to reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission is uncomfortable physically and socially. However, until effective prevention drugs and vaccines are developed, masks will be necessary to protect public health - masks simulate "herd immunity" if everyone wears them in public places. This requirement is not universally popular in the United States, where "freedom" is sometimes seen as more important than "responsibility" to others. As of May 4, 2020 there has already been a murder of a store security guard by a customer upset about mask wearing requirements, with threats of violence in other places. Whether to wear a mask or not has become partly a "culture war" divide, with liberals supposedly all on the side of wearing a mask and conservatives supposedly all on the side of not wearing a mask.

Viruses don't care about anyone's politics.

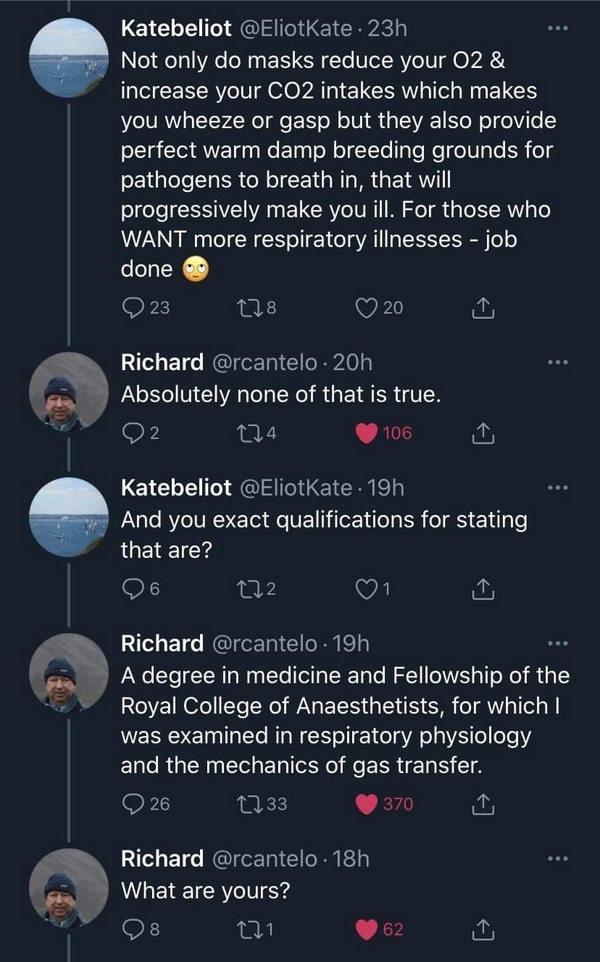

There are hoaxes floating on anti-social media claiming masks are threats to the wearers due to oxygen reduction. Some of those creating these hoaxes are full strength virus deniers and downplayers. Remember, anyone can say anything on the internet (except maybe in China, with their on-line censorship system).

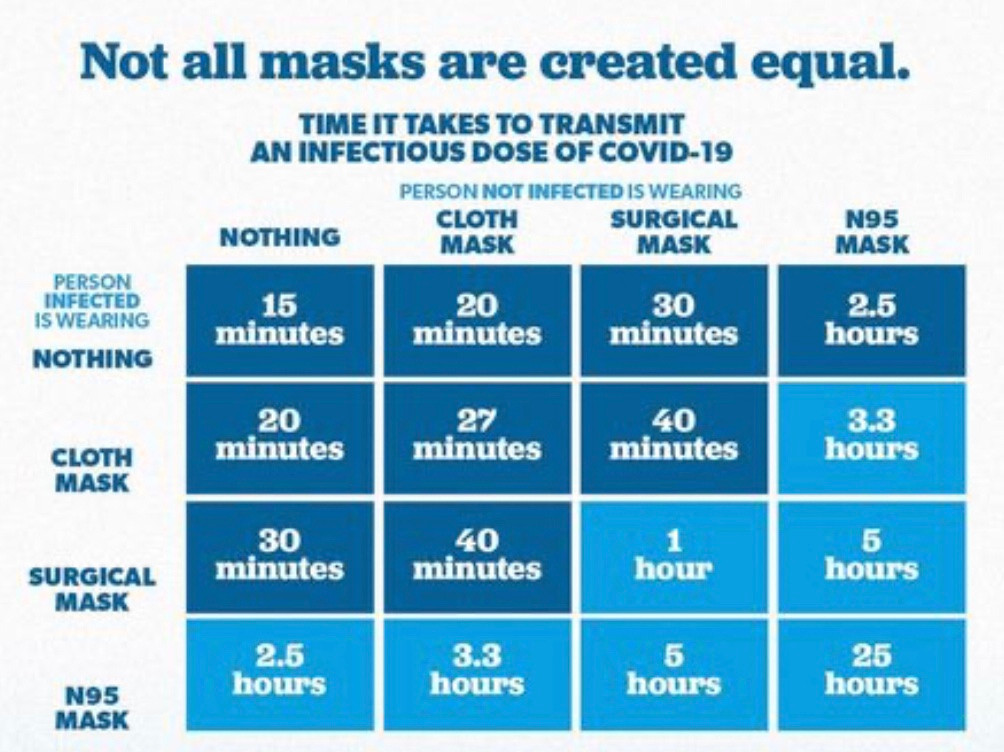

They are not perfect, especially in situations with high viral loads (coughing patients in a hospital). Taking off contaminated masks in a health care setting requires extra care. Seat belts are not 100% effective either, but it is wise to wear them in a car.

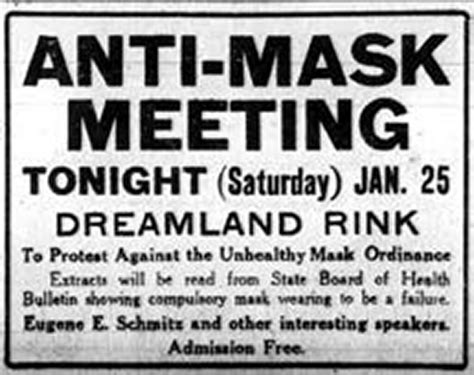

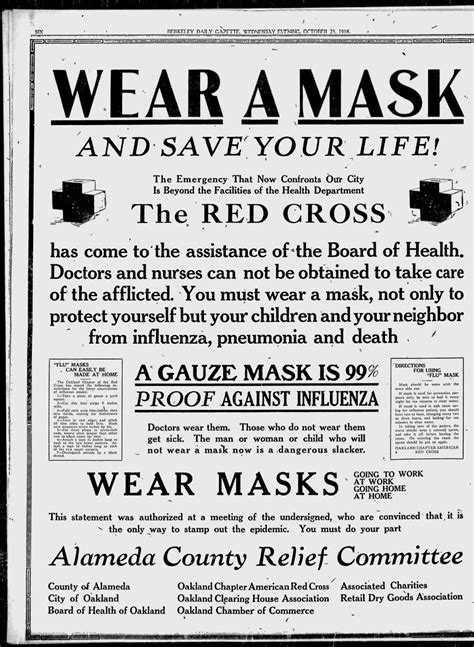

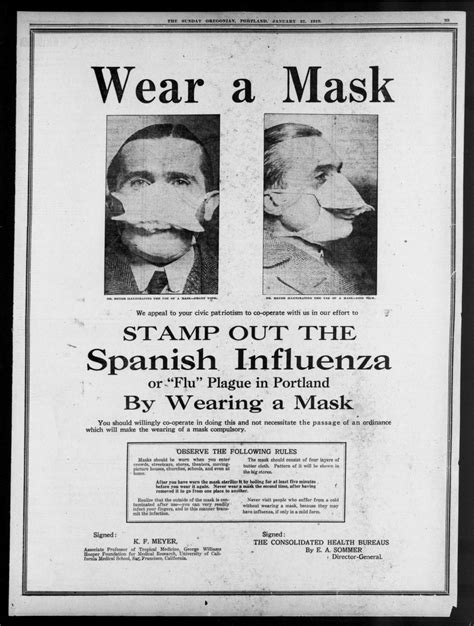

1918 pandemic

If 80% of Americans Wore Masks, COVID-19 Infections Would Plummet

Masks help stop the spread of coronavirus – the science is simple and I'm one of 100 experts urging governors to require public mask-wearing

Jeremy Howard

Distinguished Research Scientist,

University of San Francisco

May 14, 2020 8.03am EDT

On May 14, I and 100 of the world's top academics released an open letter to all U.S. governors asking that "officials require cloth masks to be worn in all public places, such as stores, transportation systems, and public buildings."

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that everyone wears a mask – as do the governments covering 90% of the world's population – but, so far, only 12 states in the U.S. require it. In the majority of the remaining states, the CDC recommendation has not been enough: Most people do not currently wear masks. However, things are changing fast. Every week more and more jurisdictions require mask use in public. As I write this, there are now 94 countries that have made this move. ....

If only people with symptoms infected others, then only people with symptoms would need to wear masks. But experts have shown that people without symptoms pose a risk of infecting others. In fact, four recent studies show that nearly half of patients are infected by people who do not themselves have symptoms.

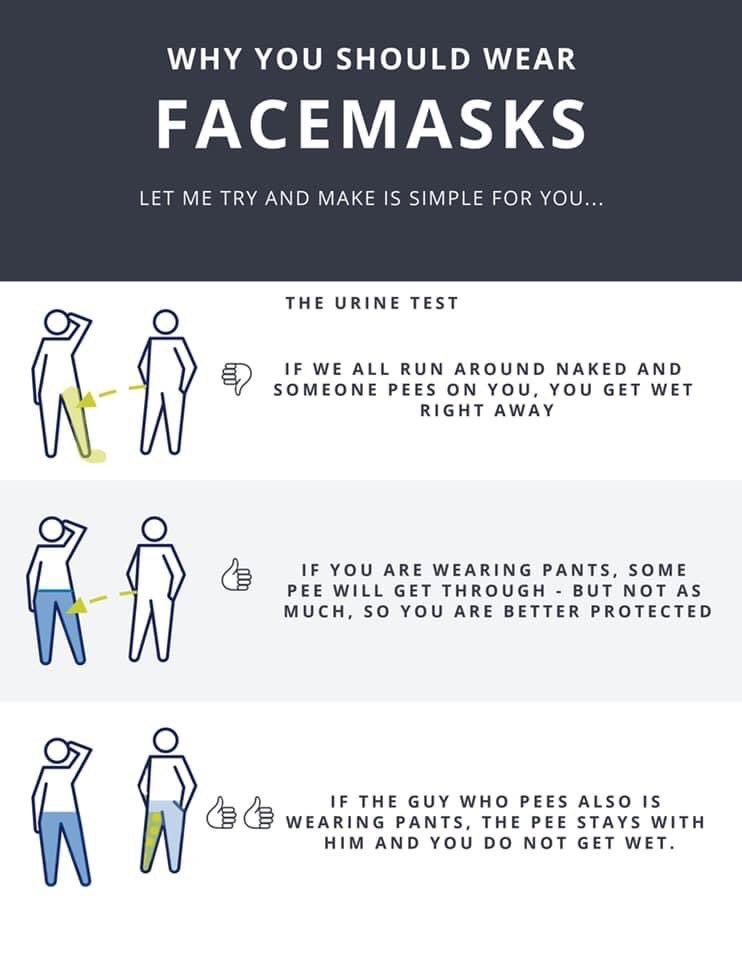

This evidence seems, to me, clear and simple: COVID-19 is spread by droplets. We can see directly that a piece of cloth blocks those droplets and the virus those droplets contain. People without symptoms who don't even know they are sick are responsible for around half of the transmission of the virus. ....

There are numerous studies that suggest if 80% of people wear a mask in public, then COVID-19 transmission could be halted. Until a vaccine or a cure for COVID-19 is discovered, cloth face masks might be the most important tool we currently have to fight the pandemic.

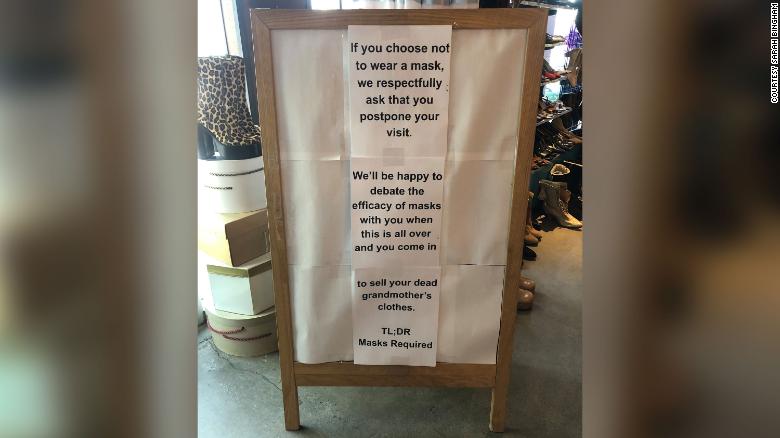

New Seasons Market, Portland, Oregon:

graphic posted at Reddit:

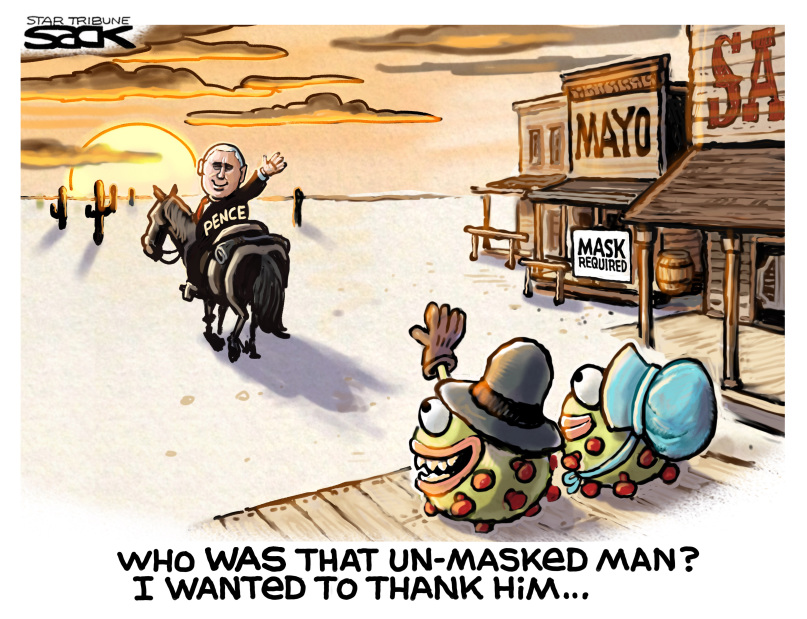

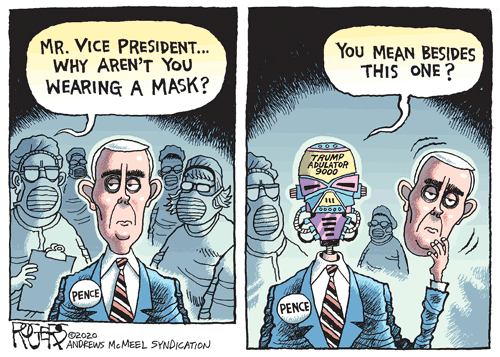

Mike Pence visited the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and refused to follow their policy that everyone must wear a mask.

New England Journal of Medicine account of a hospital having to protect its PPE from the Federal government

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2010025

In Pursuit of PPE

April 17, 2020

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2010025

To rapidly communicate short reports of innovative responses to Covid-19 around the world, along with a range of current thinking on policy and strategy relevant to the pandemic, the Journal has initiated the Covid-19 Notes series.

As a chief physician executive, I rarely get involved in my health system's supply-chain activities. The Covid-19 pandemic has changed that. Protecting our caregivers is essential so that these talented professionals can safely provide compassionate care to our patients. Yet we continue to be stymied by a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and the cavalry does not appear to be coming.

Our supply-chain group has worked around the clock to secure gowns, gloves, face masks, goggles, face shields, and N95 respirators. These employees have adapted to a new normal, exploring every lead, no matter how unusual. Deals, some bizarre and convoluted, and many involving large sums of money, have dissolved at the last minute when we were outbid or outmuscled, sometimes by the federal government. Then we got lucky, but getting the supplies was not easy.

A lead came from an acquaintance of a friend of a team member. After several hours of vetting, we grew confident of the broker's professional pedigree and the potential to secure a large shipment of three-ply face masks and N95 respirators. The latter were KN95 respirators, N95s that were made in China. We received samples to confirm that they could be successfully fit-tested. Despite having cleared this hurdle, we remained concerned that the samples might not be representative of the bulk of the products that we would be buying. Having acquired the requisite funds — more than five times the amount we would normally pay for a similar shipment, but still less than what was being requested by other brokers — we set the plan in motion. Three members of the supply-chain team and a fit tester were flown to a small airport near an industrial warehouse in the mid-Atlantic region. I arrived by car to make the final call on whether to execute the deal. Two semi-trailer trucks, cleverly marked as food-service vehicles, met us at the warehouse. When fully loaded, the trucks would take two distinct routes back to Massachusetts to minimize the chances that their contents would be detained or redirected.

Hours before our planned departure, we were told to expect only a quarter of our original order. We went anyway, since we desperately needed any supplies we could get. Upon arrival, we were jubilant to see pallets of KN95 respirators and face masks being unloaded. We opened several boxes, examined their contents, and hoped that this random sample would be representative of the entire shipment. Before we could send the funds by wire transfer, two Federal Bureau of Investigation agents arrived, showed their badges, and started questioning me. No, this shipment was not headed for resale or the black market. The agents checked my credentials, and I tried to convince them that the shipment of PPE was bound for hospitals. After receiving my assurances and hearing about our health system's urgent needs, the agents let the boxes of equipment be released and loaded into the trucks. But I was soon shocked to learn that the Department of Homeland Security was still considering redirecting our PPE. Only some quick calls leading to intervention by our congressional representative prevented its seizure. I remained nervous and worried on the long drive back, feelings that did not abate until midnight, when I received the call that the PPE shipment was secured at our warehouse.

This experience might have made for an entertaining tale at a cocktail party, had the success of our mission not been so critical. Did I foresee, as a health-system leader working in a rich, highly developed country with state-of-the-art science and technology and incredible talent, that my organization would ever be faced with such a set of circumstances? Of course not. Yet when encountering the severe constraints that attend this pandemic, we must leave no stone unturned to give our health care teams and our patients a fighting chance. This is the unfortunate reality we face in the time of Covid-19.

Andrew W. Artenstein, M.D.

Baystate Health, Springfield, MA

Disclosure forms provided by the author are available with the full text of this note at NEJM.org.

This note was published on April 17, 2020, at NEJM.org.